Blazing Youth, Or, Why Beauty Pair Should Be in the WON Hall of Fame

The BeruBara Boom, Fuji TV, and two women that changed the course of joshi wrestling forever

Alexandra Fraser is currently in the middle of a crucial and lengthy research project into the contexts and legacies of joshi wrestling in the 1970s; she previously shared some of her findings on the first Miracle Apricot Roundtable back in 2021, which discussed the peaks and troughs of joshi wrestling’s cultural relevance over the past five decades and attempted to answer the questions of whether we’re currently entering a new Golden Age. Here, she makes the case for giving two of the biggest and most impactful stars of the ‘70s their proper historical cookies.

Subscribe to Marshmallow Bomb for free to receive all our posts direct to your inbox, or donate $5 a month to access the full archive. A portion of every subscription supports Amazon Frontlines, an organisation dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to defend their way of life, the Amazon rainforest, and our climate future.

Beauty Pair are, without doubt, one of the most important wrestling acts in the history of Japanese wrestling, but their importance to the sport and the context behind their iconic status is little known outside of Japan. This is a true shame to their legacy, and reveals the limitations inherent in the the voices that foreign fans have had to rely on for news and history of joshi wrestling. Since so many fans are unfamiliar with the first megastars of joshi wrestling, I'll first briefly explain who Beauty Pair were.

Who?

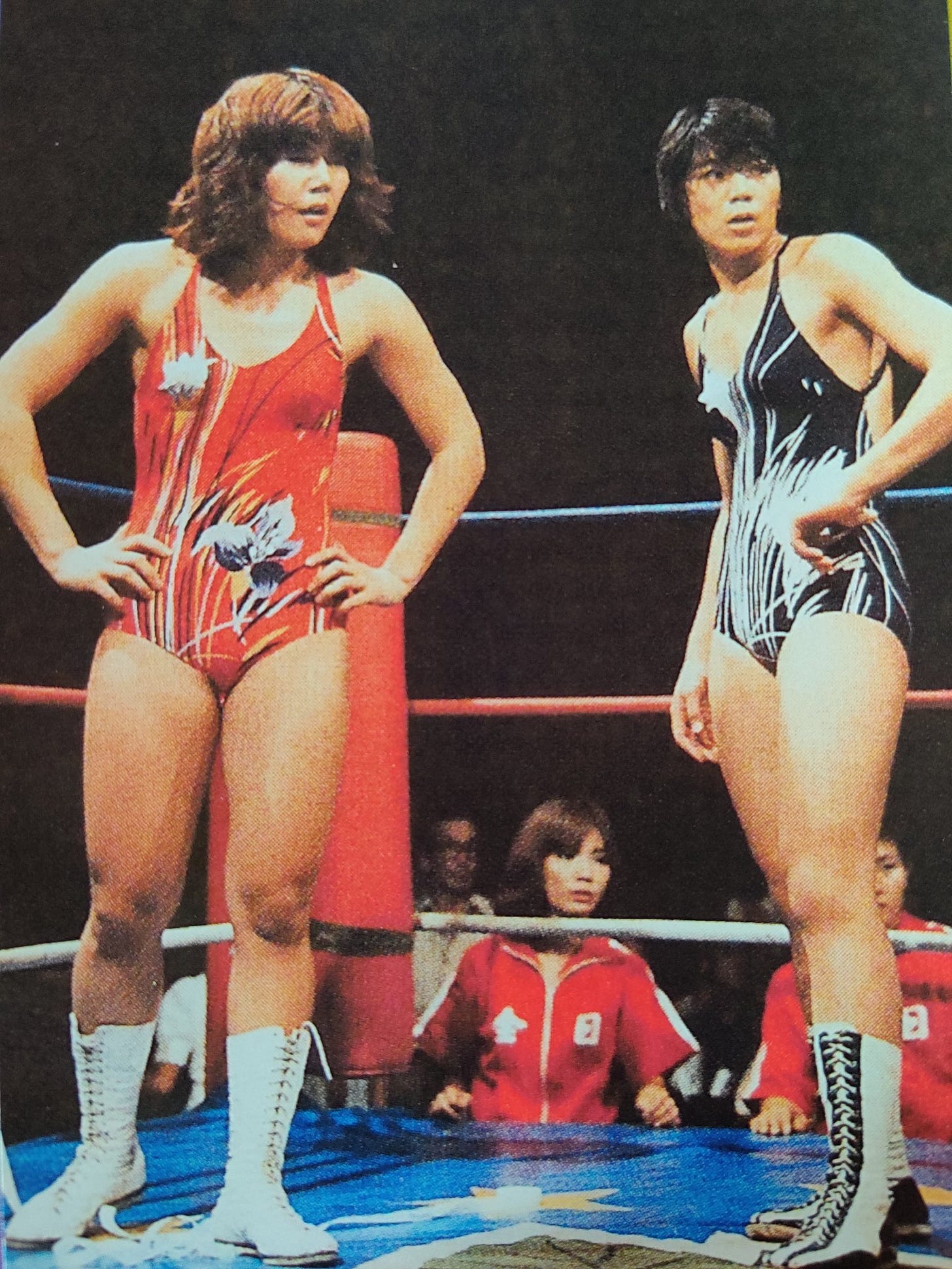

Naoko Sato (October 30, 1957 – August 9, 1999) was born in Yokohama, Kanagawa and had been active in basketball clubs since junior high school. She had enough talent that scouts were interested in signing her, but she would drop out of high school to join All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling in March 1975. Jackie would make her debut under her real name a month later on April 27, against her future tag partner, Maki, and adopted “Jackie” as her ring name in 1976.

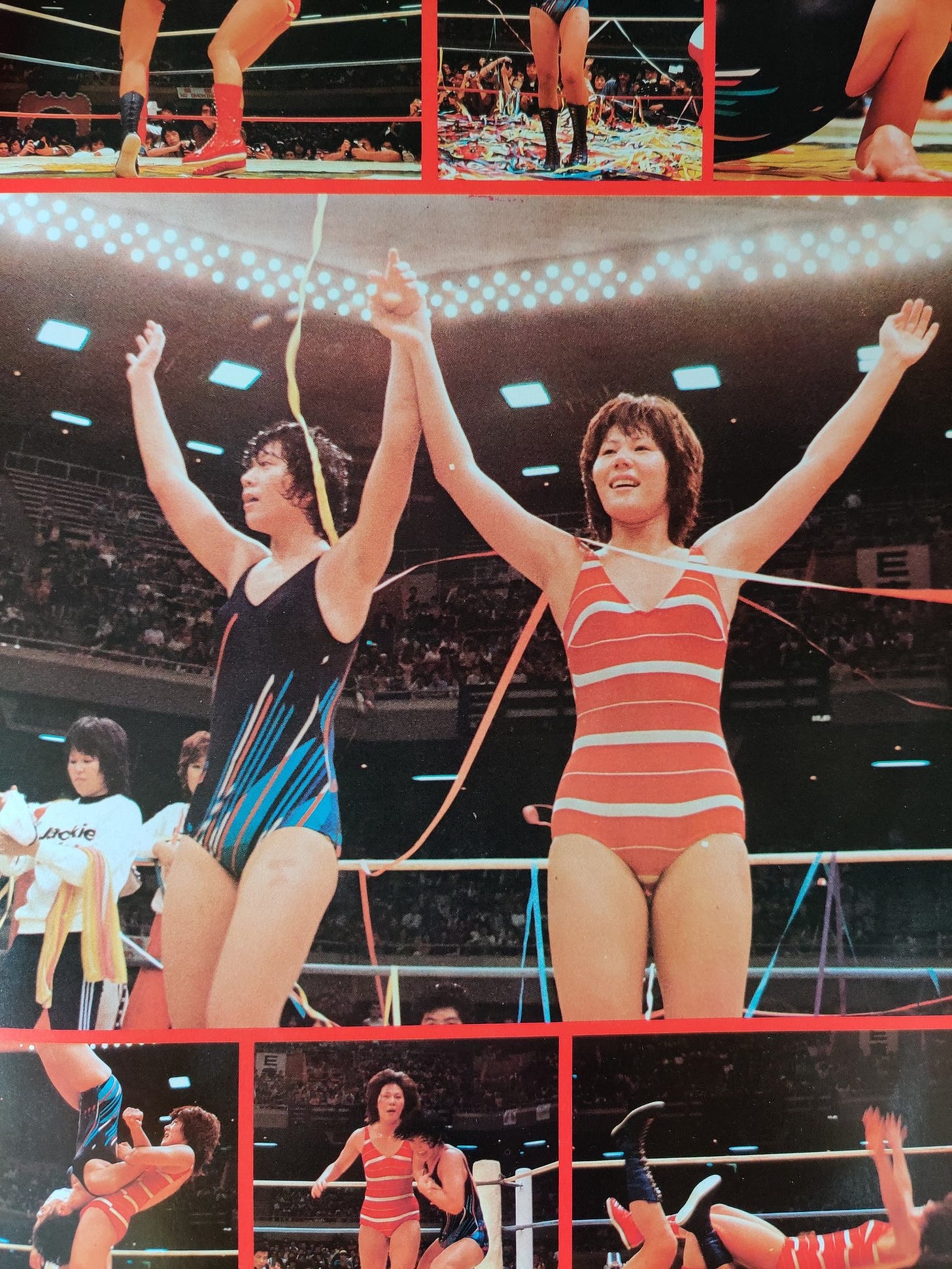

Jackie Sato would first win the WWWA Tag Championship with Maki Ueda on February 24, 1976, at Korakuen Hall, in Beauty Pair’s debut as a team. They dropped the belts to the team of Jackie West & Yukari Lynch during the spring and started their second reign as champions on July 17, 1977. Sato would defeat Ueda to win her first WWWA singles championship via decision on November 1, 1977, after a 60-minute draw at Budokan Hall, and would remain champion for 637 days. Jackie’s most famous WWWA title defense is probably the “Loser must retire match” on February 27, 1979, in which she faced her tag team partner and current All-Pacific champion, Maki Ueda, in front of a packed Nippon Budokan.

After Beauty Pair, Jackie’s AJW career focused on a long-term feud against monster heel, Monster Ripper. She also released a handful of music singles, but none of these met with anywhere near the same level of success as the singles she released alongside Ueda. After 6 years, on May 21, 1981, Jackie Sato retired from AJW as a three-time WWWA singles champion and a three-time WWWA tag champion.

Makiko Ueda (March 8, 1959) was born in the small city of Tottori, the capital of Japan’s least populated prefecture. Maki played volleyball in junior high and wanted to continue playing in high school, but between her dad wanting her to become a pro wrestler and Maki’s own desire to leave her small hometown, she dropped out of school after one year and joined All Japan Women’s Pro Wrestling in 1974. Debuting on March 19, 1975, Maki had a full year of training and was the better wrestler of the two during their run as a team. She was also the first of the two to receive a big singles push, winning the WWWA singles championship in her hometown on June 8, 1976 from the former ace, Jumbo Miyamoto.

This passing-of-the-torch moment from the ace of the previous era to one of the new stars of the sport was a touching one for both women: after the final bell has rung on her fifth and final reign, Jumbo’s contemporaries enter the ring to comfort the soon-to-retire veteran, and Maki selflessly takes a moment before celebrating and handing the trophy to Jumbo. Maki would lose the WWWA belt to Mariko Akagi after just under 200 days, and would go on to win and lose it again in 1977, this time handing it over to Sato. Her last major singles title reign came in the form of the Hawaiian Pacific title (eventually renamed the All-Pacific title), from 1978 until her retirement in early 1979.

Not only was Maki the better wrestler of Beauty Pair, she was the one holding the big red belt when Beauty Pair released their first single in November 1976. She’s also the first woman in AJW history to complete the grand slam of WWWA singles title, WWWA tag titles, All-Pacific championship. By late 1978 Ueda had multiple reasons to want to quit the company, but President Takashi Matsunaga insisted on holding a definitive, era-ending match between herself and Sato before letting her go. On February 27, 1979, Maki lost her challenge against Jackie, and her career wrapped up after nearly 4 years.

Why?

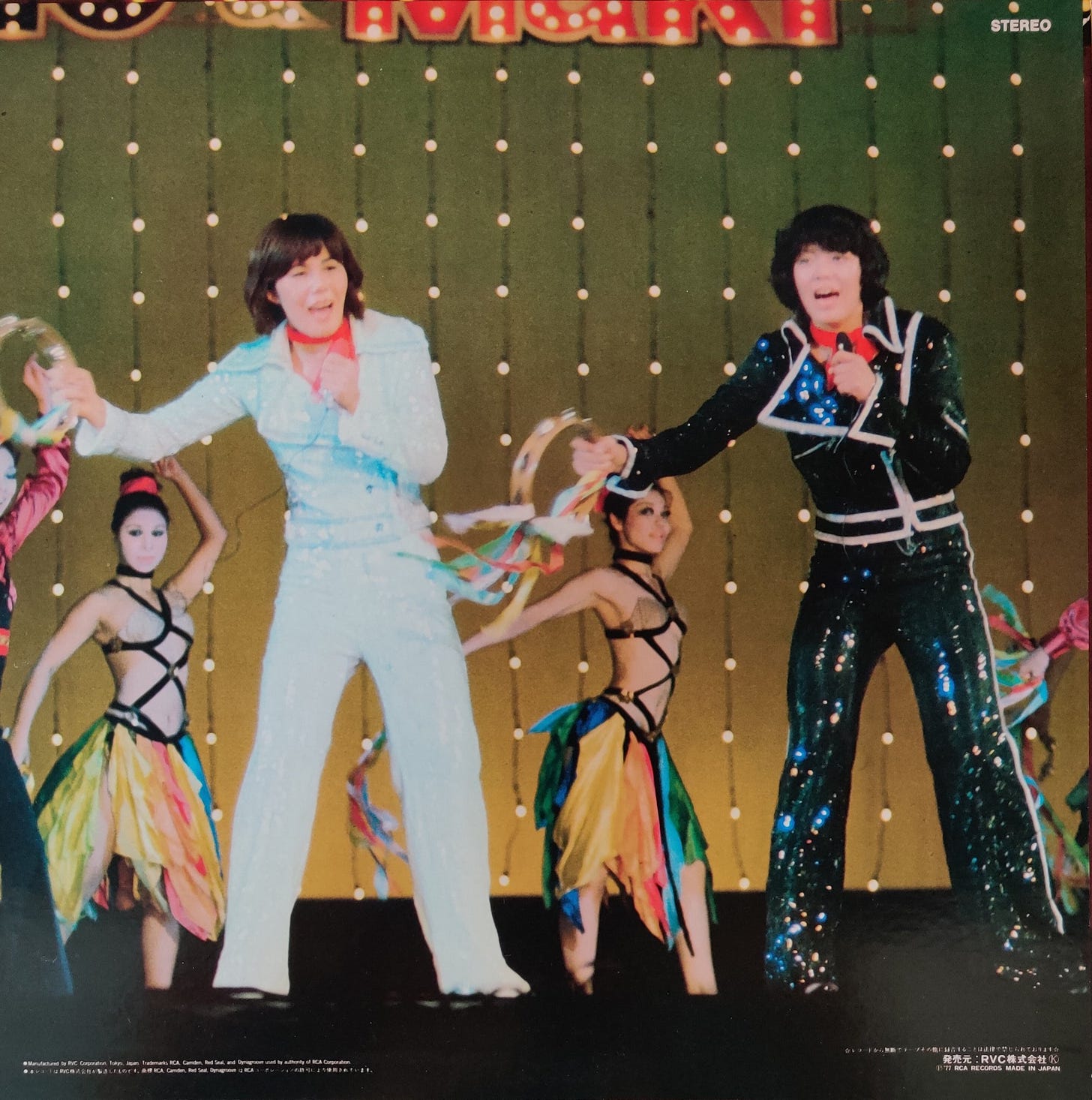

The first important question to answer is why did a Fuji TV producer, Hitoshi Yoshida, go to AJW with the express purpose of finding two androgynous-looking wrestlers that could sing to put together in a tag team? The answer is clear: to compete with rival television broadcaster, NHK, and their telecasts of the wildly popular Rose of Versailles plays staged by the all-female Takarazuka Revue between 1974 and 1976.

The Rose of Versailles was published in Margaret magazine from 1972 to 1973 and remained a cultural phenomenon for the rest of the decade. Oscar Francois de Jarjayes and Marie Antoinette’s adventures and battles against the backdrop of the French Revolution captured the imaginations of young women and girls all over Japan and made many companies and manga publishers take note of the commercial viability of the shoujo genre. The 1970s would see a total of five different Rose of Versailles plays directed by Shinji Ueda and Kazuo Hasegawa, and the “BeruBara Boom” would be one of the most profitable and important periods in the Takarazuka Revue’s near 120 years of existence.

NHK, the home of Takarazuka Revue telecasts since the broadcaster went live, also got to reap the benefits of the BeruBara Boom with their telecasts of the 1970s productions. This cut into a demographic that Fuji TV had been targeting since they first struck up a TV deal with AJW based on the appeal of their then-top star, Mach Fumiake. During the Golden Sixties, housewives became key consumers for entertainment companies due to their increased spending power, and with the increased spread of television the sixties housewife was now more exposed to the power of advertising than her mother’s generation. With husbands spending most of their time at work and after-work functions, TV producers started to focus on attracting housewives and children, who were more likely to be watching weekday primetime brodcasts; Fuji TV saw a teenage singer making her debut in wrestling, and decided to act.

Mach Fumiake had finished in second place on Nippon TV’s talent show Star Tanjou, giving her some ready-made celebrity status, but while her debut match was also broadcast on Nippon TV, the station didn’t seem interested in giving AJW a regular slot on their airwaves. Instead, Fuji TV swooped in and made a deal: there must be at least one singing performance for each AJW broadcast, the wrestlers should have colorful and fun entrance clothes, and there must be nothing to tarnish the new “healthy” image that the station wanted to create for joshi wrestling. April 1975 marked the beginning of Fuji TV and AJW’s long-term relationship; when Fumiake retired in 1976, Fuji TV and AJW got straight to work on creating a pair of new top stars to snare the BeruBara Boom audience.

So how popular were Beauty Pair? It’s hard to compare Beauty Pair’s popularity to anything in men’s wrestling because they weren’t seen as popular athletes but were instead viewed as idols that made joshi wrestling a cultural cornerstone. Mach Fumiake wrestled from 1974 to 1976 and was the first joshi wrestler to become a celebrity; her career would help plant the idea in the general public’s mind that joshi wrestling was a gateway to music stardom, and Beauty Pair further cemented that concept while also mobilizing an entire generation of teen girls.

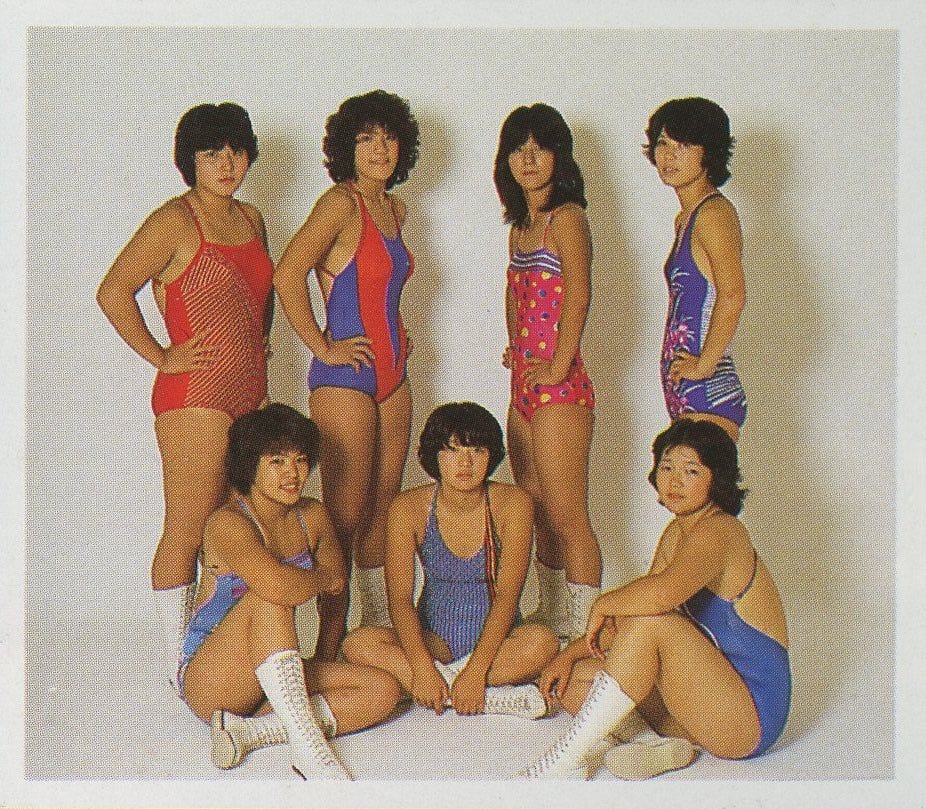

When Maki Ueda joined AJW in 1974 the company didn’t yet hold yearly auditions, and lacked a formal pro-test for rookies: hopefuls would simply send in an application with some basic information attached and would then be invited you to the dojo for a tryout. Sato made her debut after just a month of training, but the mammoth popularity of her act forced the company’s hand in tightening application requirements and creating an actual audition procedure. The number of applications was so high (600 for the 1977 auditions) that Fuji TV, no doubt delighted by the instant runaway success of their venture, opened their own doors to these audition sessions, hosting them from 1977 all the way through to 1990.

Beauty Pair were the creation of Fuji TV producer, Hitoshi Yoshida. He’s also the man responsible for getting Beauty Pair a record deal with RCA, and for producing their concert shows, The Beauty Pair Show. Starting on July 15, 1977, AJW’s slot on Fuji TV was moved to 7:00 on Friday evenings and at one point pulled higher ratings than men’s wrestling on other tv stations, but Zen Nihon Joshi Puroresu Makkana Seishun (“AJW Blazing Youth”) wasn’t the only place on TV that fans could see Beauty Pair. The success and popularity of Jackie and Maki was also forged through appearances on Fuji TV’s music chart show, Yoru no Hit Studio, and other variety shows on the network.

At the peak of their popularity Beauty Pair were receiving a reported 3,000 fan letters a month. They also starred in their own movie in the summer of 1977, released six singles and a handful of albums, and had two live variety shows at the Asakusa International Theater. They won the Special Award at Fuji TV’s FNS Music Festival in 1977, and had a seemingly endless supply of merchandise ranging from playing cards, stickers and t-shirts to posters, memo notebooks and fan magazines. Beauty Pair, like Mach Fumiake before them, helped legitimize joshi wrestling to the Japanese public, making it not only socially acceptable but a cool and desirable profession for teen girls to pursue. They convinced an audience who had never considered stepping foot in a gym to buy tickets to a wrestling show: at first their fans would cheer during the singing and stay quiet during actual matches, but by late 1977 the Beauty Pair faithful were busy cheering on their heroines as they fought the villainous Black Pair.

The ‘loser must retire’ match between Jackie and Maki, three years after their debut as a team, was big enough to draw a sellout crowd at Budokan Hall. Beauty Pair’s impact on the sport was twofold. First, they made a generation of girls seek out wrestling not just as fans but as potential performers: they’re the reason we get Jaguar Yokota, Devil Masami, Mimi Hagiwara, Chigusa Nagayo, Lioness Asuka, Dump Matsumoto, and more in the years that follow. Second, they contributed as much as anyone to erasing the Japanese public’s idea of joshi wrestling as a form of erotic entertainment for men; the androgynous look of the Pair and their refusal to play to the male gaze were key factors in making them popular with young women and girls. The history of joshi wrestling in the late 70s is a single thread and that thread is Beauty Pair: Crush Gals, and everything that come after them, exist because of Beauty Pair’s legacy. To have the wrestlers of the 80s represented without acknowleding the team that inspired them to begin their careers tells an incomplete story: Beauty Pair deserve a place in the WON Hall of Fame.