It’s finally time to reveal the results of my very scientific survey into the top workers of 2020. Here are the five wrestlers I’ve written about more than any others this year, which in my way of doing things works at as something approaching “best”. Unsurprisingly, they are all drawn from two promotions - Gatoh Move and Ice Ribbon (Sakuraism remains undefeated).

I hope you’ve enjoyed Go Go! 2020! Thanks for all your attention throughout this busy month, and I look forward to resuming normal service with the Flupke’s Month in Wrestling: December newsletter in the coming days. If you haven’t already, why not take the time to check out my previous Go Go! pieces - on my top 5 matches from the archives, top 5 under-the-radar bangers, top 5 wrestlers not from Gatoh Move or Ice Ribbon and my matches of the year - before reading this one?

Done? Great. Here they are then…

5) Risa Sera

2020 could be Risa Sera’s last full year as a wrestler, and it feels like the one where she finally found her feet, finally became a completed version of the wrestler she’d been trying to become since she first persuaded Ice Ribbon to let her fight deathmatch guys in 2015. In August I wrote at length about how a lot of my appreciation for Sera’s hardcore matches happens on a meta level - I’m “in love with the idea of Sera’s absurd love of putting herself through horrific challenges every year on her birthday”. I’m really just happy for her to be there. I compared the experience of watching Sera don her deathmatch garb to going to see a friend’s band play live - “there may be something lacking from the spectacle on a certain, suspension-of-disbelief-y kind of level but there’s an equal and opposite attachment on a more intimate and grounded level” (I cannot state enough how aware I am that Risa Sera is not my friend, but Ice Ribbon’s promotional philosophy is in keeping with most of the rest of joshi wrestling in fostering these kinds of parasocial feelings).

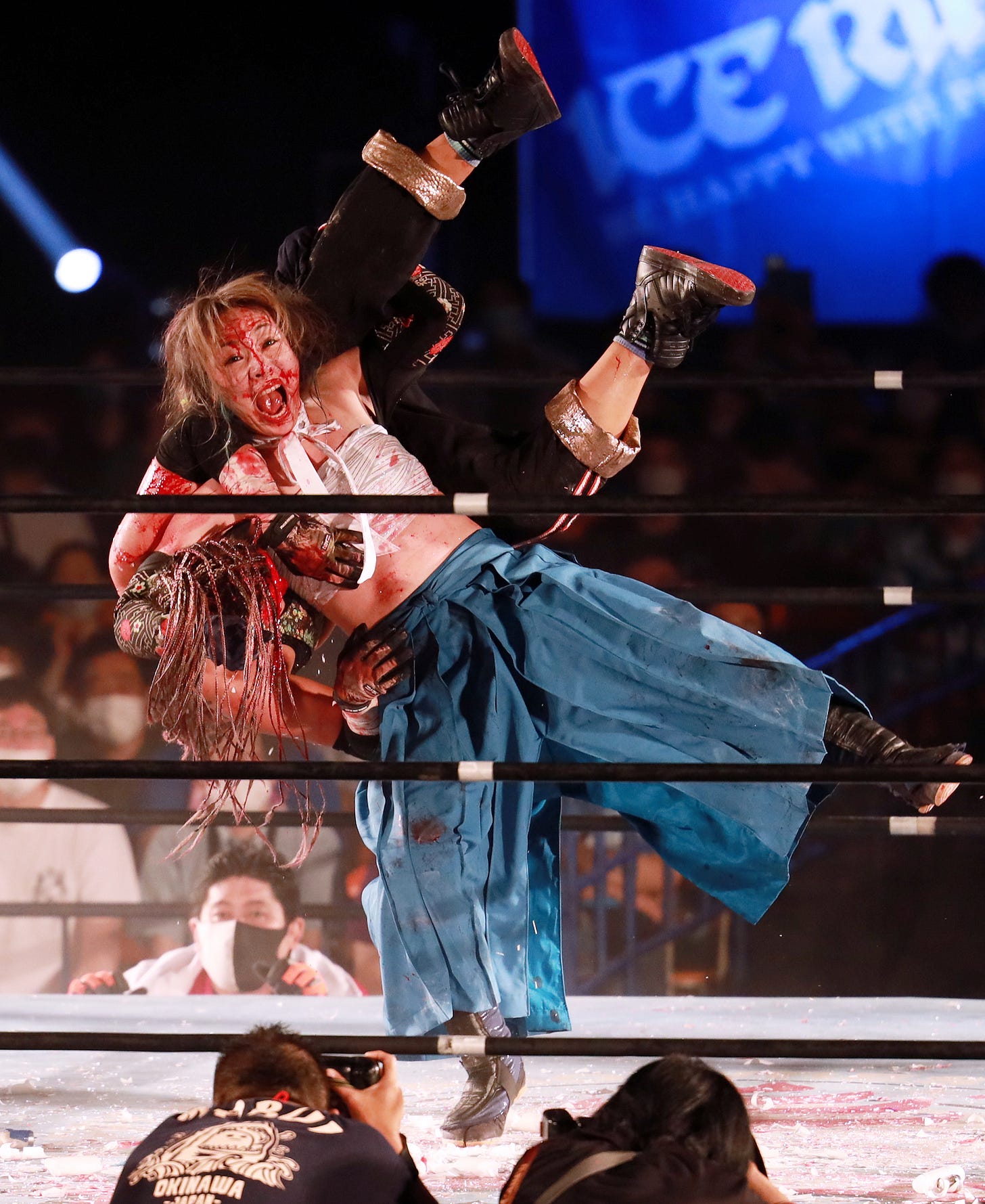

Sera’s work this year turned all this on its head. By August, she felt every bit as much the accomplished deathmatch performer as her opponent in the match to decide the inaugural FantastICE Champion, FREEDOMS regular Rina Yamashita. That match was a revelation, because it finally put Sera in a context where deathmatch rules carried real stakes - this was no longer the Sera that mucks around with Abdullah Kobayashi on her birthday, this was a battle-hardened Sera looking to bring her skills with a fluorescent light tube to bear in a hunt for singles gold. The ringside photographs taken of this match are some of the best taken all year, because they show Sera perfecting an iconography that had previously come across as a kind of cosplay - this tall, beautiful, elegantly-dressed woman, wielding baroque instruments of carnage, covered head to toe in her opponent’s blood.

In the final third of the year, Sera’s role shifted again, as she took stewardship over a new part of Ice Ribbon’s programming that, once it was introduced, immediately felt like something that had been there all along. At time of writing, Sera has defended the FantastICE title six times, and is yet to repeat a stipulation. She’s defended it in a two day-long “Baseball Rules” match against Akane Fujita at Ueno Park. She’s defended it under “No Rope Lumberjack Rules” against Syuri, a match which in part was an excuse to toy with the brilliant comic premise of Sera having to beg Maya Yukihi’s Rebel & Enemy stable to accompany her to ringside, since nobody else was available). She’s retained by impaling Matsuya Uno on a bamboo skewer board in a “Give Up Only” match. She put it on the line in the main event of her annual Risa Sera Produce show, bravely declaring that she’d forfeit the belt if she couldn’t make it to the end of the hour-long Iron Woman Match in one piece. She’s used the title as the backdrop to a first Ice Ribbon appearance for Maya Yukihi’s “Dark Snow” alter-ego, and to give hugely promising new rookie Yuuki Mashiro her first official title shot. All in all, she’s represented Ice Ribbon at its best - as a place of invention and imagination and variety and diversity, the sort of place that allows wrestlers to be the kind of wrestlers they want to be, even if that means jumping knees-first off ladders into piles of broken glass.

4) Lulu Pencil

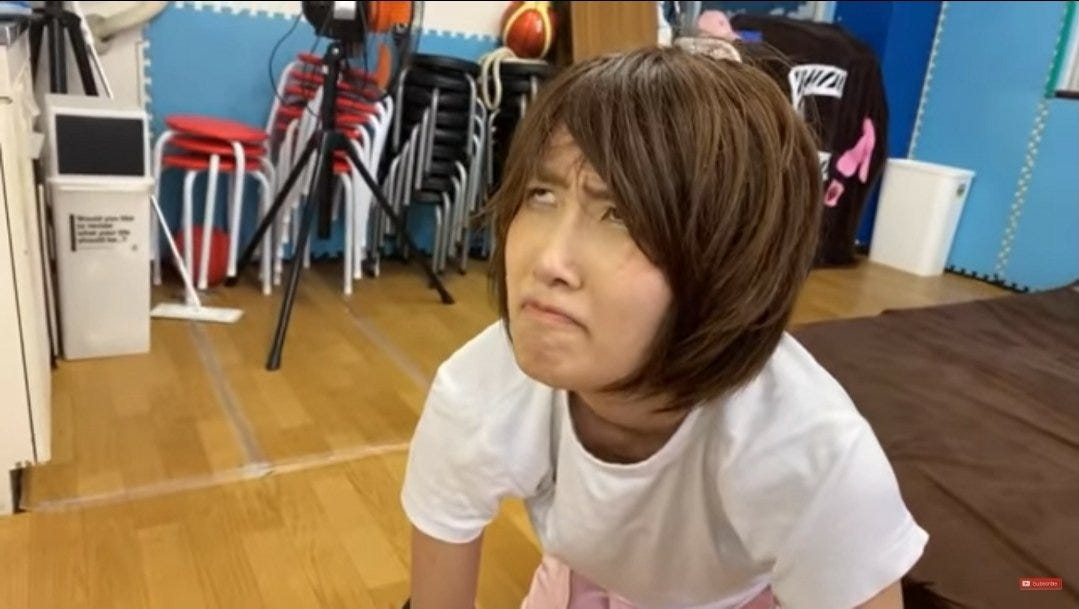

It simply can’t be overstated that Lulu Pencil conceded eight falls inside three minutes in her first exhibition match, a match which is part of Gatoh Move lore because it was uploaded to YouTube immediately after it had happened. It also can’t be overstated that Lulu Pencil has still not won a match. Her journey to legitimacy as a pro wrestler is an exhaustingly long one, and it is still nowhere near complete. But early on in her training, Lulu wrote that,

Someday, I want to find a different kind of strength in my own fight, a strength that’s distinct from what the rest of the world considers “good”, or something different from strength altogether. That’s what women’s pro wrestling means to me, and it’s why I think people all over the world need it right now.

The idea that there could be a special kind of power in vulnerability, in weakness, in crappiness, in values distinct from power itself, is one that’s accepted in other artistic media - music, film, literature - with relatively little controversy. But never before in pro wrestling have I seen a performer that embodies this ethos so successfully as Lulu Pencil does (Maki Itoh is her only real rival on this count). It’s a bold gesture, not just to brush against the grain of the idea that compelling wrestlers need to be “good”, but also to reject the notion that any weakness is wrestling is always a prelude to strength, conventionally imagined; that arcs of personal development should always end with the underdog standing on top of the mountain.

It’s a gamble, but it’s a gamble that has paid off - Lulu became one of the most popular wrestlers in Gatoh Move from the second she showed the world who she really is, and her appeal remains undimmed even after a year and half of wall-to-wall defeats. In losing to Chris Brookes in my Match Of The Year in November, she gained more than a lot of wrestlers would gain in the biggest of career milestone payoffs - she came away with a nuanced sense that she’s her own woman now, that her endless suffering in pursuit of this painful art has meaning, purpose and value. What could be more powerful than that.

3) Tsukushi Haruka

The picture above shows the aftermath of what might be the highlight of my favourite singles match of 2020. Tsukushi Haruka has just clocked Suzu Suzuki in the face with a closed right fist, a final, brutal flourish to a series of strikes that borders on the hysterical. Her face tells you everything you need to know - there’s a terrifying self-possession and confidence there, but also a sense that she’s barely keeping a lid on forces that could tear herself, her opponent and Korakuen Hall to pieces. Tsukushi’s whole identity as a wrestler in 2020 is here. She’s a near-10 year veteran and a senior figurehead of Ice Ribbon - a multiple-time singles and tag champion, a head trainer at the dojo, and now the producer of its P’s Party offshoot - in whose tiny frame beats the heart of the most savage and brattish of rookies.

Purely focusing on “bell-to-bell”, leaving aside pushes and angles and wider importance in context, Tsukushi is probably my favourite wrestler in the world in 2020. She never had a match that was less than very good, and she had plenty of great ones - the title match with Suzu in September is the one undisputed highlight, but there was also the IW19 Title Tournament time limit draw against Hamuko Hoshi and Risa Sera in May; the clashes with Honori Hana in P’s Party in October; the brief, decisive battle with Kakeru Sekiguchi in the 5-on-5 Ice Ribbon vs. ActWres girl’Z elimination gauntlet match at their cross-promotional show in November. With Ice Ribbon opening up more and more of their content to international audiences this year, Tsukushi was somebody I watched a lot of - and it takes a special kind of wrestler to dazzle every time, wherever they’re positioned on the card, from the most throwaway of dojo show openers to the main event at Korakuen Hall. She may not have received the success and focus this year of some of the other wrestlers on this list - missing out on the coveted IW19 Championship final after losing a fan vote, dropping the tag titles to Frank Sisters at the Buntai, providing fodder for Suzu’s first successful defence of the ICE x Infinity title - and her role has largely been that of a supporting character. But there’s almost no in-ring performer I’d trust more to make me forget my worries, and to remind me why I fell in love with wrestling in the first place.

2) Mei Suruga

Mei Suruga was a completely magnetic presence from the moment she debuted in pro wrestling, but 2020 was the year she went supernova, easily occupying the role of top star (if not always primary protagonist) of the promotion that gained the most from the shake-up of the Japanese wrestling scene taking place in the shadow of the pandemic. Until recently it might have seemed like a gesture of obtuse hipsterism to declare Mei one of the best in the world, but in light of Gatoh Move’s increased international exposure in 2020, such a thing now barely seems like a hot take at all. In light of Mei’s almost universal popularity, I want to hand over the rest of this entry to another writer: Sarah Kurchak, author of I Overcame My Autism and All I Got Was This Lousy Anxiety Disorder: A Memoir as well as a particularly great feature on Lulu Pencil, who sums up the importance of Mei’s 2020 better than I ever could:

A while ago, I read an article about the midtown Toronto apartment where Glenn Gould spent most of his adult life. In it, the building’s longterm landlord confessed that she used to sneak onto the roof, sit above the Canadian classical phenom’s window and listen to him play piano every night. “He never knew I was up here, or else he would have been angry with me, I suppose,” she mused. “But I had the moon and the stars and his music and there was nothing more beautiful.”

I’ve thought about this a lot since. Not just what a pleasure it must have been to hear Gould play at all, but what a unique gift it must have been to witness an actual prodigy consistently honing their preternatural skills and further developing their already remarkable craft in their own environment. It struck me as the most incredible glimpse into the artistic process.

And I got to witness it for myself in wrestling this year.

I experienced a taste of it in 2019 when I became a new Gatoh Move convert. It was clear to me within a couple of matches that the promotion’s star rookie, Mei Suruga, was a prodigy and that the promotion’s primary venue was a mix of Suruga’s home base and her primary instrument. (I even referred to Ichigaya Chocolate Square as Suruga’s Stradivarius in a blurb for FanFyte back in February.) The advent of ChocoPro gave me a deeper and more consistent insight into her immense physical and mental skills as a wrestler, though. And their continuing evolution.

Since March, anyone with YouTube access has been able to watch Mei Suruga wrestle multiple times a week in the Ichigaya space — and, occasionally, its general surroundings. We’ve watched her tackle different styles, tones, emotions, and angles. Characters, too, if you count Lettuce-chan. We’ve watched her work with and against ChocoPro’s exceptionally clever and talented regulars and an impressive list of guests. We’ve watched her work through seemingly endless variations on her move set and refine everything from her submissions to her defenestration game. In essence, we’ve watched an already prodigious talent in constant development for nine months now.

Such an insight into a brilliant artist’s creative process would always have been a blessing. In a year where so much has felt dark and impossible, though, watching this combination of raw talent and dedicated work glow a little brighter each week has felt especially rewarding. We’ve had our screens and Suruga’s wrestling and there really was nothing more beautiful.

1) Suzu Suzuki

How do you top all of that? How is it that I’m able to line up these four wrestlers, each prodigious in their own right, pour every kind of praise on their work, and then say that Suzu Suzuki had a better year than all of them? It’s simple really: the other wrestlers on this list may have made me laugh, cry, shriek, but none of them made me hop around my living room like a mad kangaroo, punching the air like I’d just seen Teddy Sheringham equalise against Bayern Munich in 1999, or Jermaine Beckford complete his hat-trick against Swindon in 2015. None of them had arcs that robbed me of so much sleep, and rewarded me with so much joy, as Suzu’s run to the ICE x Infinity title did.

A brief detour into autobiography - one day last year I was on my way to a therapy session when I caught myself welling up to Sareee’s theme song. I brought it up in the session, because it doesn’t seem like a completely normal thing to do, crying to pro wrestling entrance music. Over the conversation that followed, something became clear to me - pro wrestling heroes are aspirational figures to me because everything they do is in an emotional high key. Blood and fury, death or glory, the race to the prize and the closure of finally winning the big one. Wrestlers don’t dwell in the muddy pits of ordinary feeling. When they are dejected, they cry; when they are angry, they fight; when they are brave, they win. In a world of greys, wrestlers paint with the primary colours of the human heart. I clearly need those primary colours in my life, and this year nobody made better use of them than Suzu.

With the benefit of hindsight it’s easy enough to say that Suzu was earmarked for that Buntai win all along, but so many things got in the way before we arrived there. She was supposed to debut at the Buntai in 2018 - cue an unlucky bike accident, which she eventually made hay out of, debuting at Korakuen Hall half a year later with a gimmick and catchphrase inspired by bicycles. She kept the gimmick right up until this February, when she marked the occasion of her “graduation” with a ten-bell salute for her trademark bike bells. Then, having debuted a new, more mature look and moveset, and having beaten company Ace Tsukasa Fujimoto with them at Korakuen in March, she was supposed to face Maya Yukihi for the title in Ice Ribbon’s final show at the historic Yokohama venue seven weeks later. Fate intervened again - the Buntai show was pushed back to later in the year, the title match was rescheduled for a smaller show in mid-June, with Suzu emerging unsuccessful in her challenge.

You almost couldn’t have scripted it better. Suzu was pushed fast - not out of step with her talents, but still fast. The frequent strokes of bad luck acted as a counterweight to all of this, creating a real hunger for this anointed future Ace to claim her birthright. Suzu played her part of challenger brilliantly well too, using any opportunity she could get throughout this uncertain period to cut promos on Yukihi, even when the date of their rescheduled title match was still unconfirmed. The June match wasn’t to be Suzu’s coronation, but when the Buntai show was announced as going ahead in August, with Suzu once again challenging for the belt, there was little doubt that this was to be her moment.

Or, there should have been. But for me, having enjoyed Suzu’s work since day one, having watched her morph in relatively short order from a goofy rookie with a surprisingly legit German Suplex into an obvious future face of the promotion, the question of whether Suzu would actually seal the deal this time felt as nervy and high-pressured as any outcome in real sports. I’d backed her from the beginning - I’d bound up my own emotional satisfaction with her performances of struggle and triumph, and I needed this payoff because I needed this to be one of those pictures painted in primary colours. So much so that I didn’t even really enjoy the match in question; I watched it dry-mouthed, heavy of stomach, wincing at every perceived hint that the momentum would ultimately swing in Yukihi’s favour.

The relief I felt when Suzu won was almost ecstatic. Theoretically, wrestling should reward those who put themselves through the emotional ringer like this on a more-or-less predictable basis: there’s usually a right and wrong time to pull the trigger. But it’s rarely that straightforward - there’s injuries, company politics to consider, the desire to eke out storylines longer in order to sell more tickets. Here, in a pretty rare turn of events, I’d followed a wrestling angle from its earliest origins to its eventual climax, staying invested the whole time and, most importantly really caring who won. There’s basically nothing else in wrestling fandom that can touch that.

If all this sounds like it’s simply a question of positioning and timing, that I should be commending Ice Ribbon more than their booking than Suzu for her wrestling, that’s because I haven’t gotten to the bit that comes next yet - Suzu’s string of successful defences in the final third of the year. These matches - against Tsukushi, Haruka Umesaki and Tae Honma - as well as her singles battles with Tomoka Inaba, Risa Sera and Masashi Takeda, all spoke of a performer with levels of skill and confidence to match the faith that Ice Ribbon have placed in her. Every match reveals a wrestler capable of shouldering the weight of her main event role without reverting to rote ideas of what a main event match ought to look like. It seemed a long time in coming, and it felt like a massive culmination when it arrived, but the Buntai match wasn’t really the end of anything, it was just the beginning - 2020 has taught me the futility of making predictions, but even so, 2021 looks like being Suzu’s to lose.