Imaginary Chokeslams: Wrestling with Salman Rushdie

The first - and quite probably only - comprehensive analysis of Salman Rushdie's pro wrestling references

Subscribe to Marshmallow Bomb for free to receive all our posts direct to your inbox, or donate $5 a month to access the full archive. A portion of every subscription supports Amazon Frontlines, an organisation dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to defend their way of life, the Amazon rainforest, and our climate future.

There aren’t many literary works out there that are centred around pro wrestling (with some notable exceptions), but quite a few novels by well-known authors reference it at points. The prologue of Koushun Takami’s highly influential pulpy classic Battle Royale explains the titular killing game by describing a battle royale at an AJW show, name-checking dozens of famous Japanese wrestlers including Mitsuharu Misawa, Toshiaki Kawada, Hayabusa, Tatsumi Fujinami, the Road Warriors, Aja Kong, Bull Nakano, Dynamite Kansai, Akira Hokuto and Cutie Suzuki. The inciting incident that sets the title character off on his John Hancock-collecting odyssey in The Autograph Man by Zadie Smith is a trip to see Big Daddy wrestle Giant Haystacks. As soon as the action in Pachinko by Min Jin Lee, a brilliant and moving novel about generations of a Korean immigrant family in Japan, shifts to the JWA era, we are treated to a mention of Rikidozan.

As a wrestling fan with an interest in literature, I’m forever on the lookout for nods to the greatest sport in the world. In the course of my time researching a PhD thesis on biopolitics (don’t ask) in the novels of Salman Rushdie I was delighted to discover not one but several references to professional wrestling in the renowned ayatollah-botherer’s corpus.

Rushdie’s work has been described by many critics as a form of Menippean satire, defined by the scholar Howard Weinbrot as “a kind of satire that uses at least two different languages, genres, tones, or cultural or historical periods to combat a false and threatening orthodoxy”. Put simply, he loves an allusion, whether to high culture or pop culture. He doesn’t always get them right (I still haven’t forgiven him for confusing a queen sacrifice and a Queen’s Gambit in 2017’s execrable The Golden House; it’s really easy to Google!) but you can’t understand Rushdie’s fiction without getting your head around the ways in which he deploys them to serve his narrative.

As far as I know, nobody has ever done a comprehensive survey of Rushdie’s pro wrestling references, and seeing as he’s got a new book out, what better time? (I haven’t read it yet, but it’s set in the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, so I imagine Triple H won’t be cropping up). There aren’t many topics on which I can claim to be possibly the most qualified person on the planet to write, but this is one of them. Let’s dive in, shall we?

India has a long history of pro wrestling that is, for the most part, little-known in the West. Amritsar-born Ghulam Mohammad Baksh Butt, known as The Great Gama, was a celebrated amateur and professional grappler in the early decades of the twentieth century, fighting an estimated five thousand matches and winning nearly every single one, even taking world champion Stanislaus Zbyszko to a draw in London in 1910. In more recent times, wrestlers from India (The Great Khali, Satnam Singh, Mahabali Shera and Tiger Jeet Singh) and from the Indian diaspora (Jinder Mahal, Rohit Raju and The Bollywood Boyz) have found success in North America to varying degrees, with some even winning world heavyweight titles. Over in Japan, Tiger Jeet Singh carved a niche for himself as a notorious deathmatch wrestler in promotions such as FMW and IWA Japan, and in the last few years Uttar Pradesh native Baliyan Akki has become a key part of cult micro-indie Gatoh Move both in the ring (or mat, I guess) and behind the scenes.

This is not to say that India is devoid of its own wrestling scene. The invaluable WrestleMap resource shows a handful of extant indie promotions in the country, mostly based in Delhi or Kerala. In 2011 TNA made a move into the Indian market with Ring Ka King (literally, “King of the Ring”), a co-production with the TV channel Colors, featuring a combination of TNA and Indian wrestling talent. It only lasted one season before being cancelled due to low ratings (in Indian terms this meant a mere ten million viewers), but was a fun, digestible watch that provided arguably better fare than Impact usually served up at that time. The local wrestlers adopted gimmicks like rickshaw driver tag team Pathani Pattha, the masked duo Mumbai Cats, hapless MMA fighter Max B, the impeccably dressed commissioner Jazzy Lahoria and his military bodyguard Deadly Danda, while Scott Steiner went around cutting promos calling the Indian fans “white trash” and teamed up with Abyss to terrify the Pune crowd so much that they literally fled for their lives. The series culminated with home babyfaces winning the belts from the villainous RDX faction (named somewhat tastelessly after the explosive used in the 1994 Mumbai bombings), and a match in which Jeff Jarrett – come on, who else were they going to get to lead the heel stable? – went to a no contest with Test cricketer Harbhajan Singh. Ring Ka King absolutely ruled, guys.

At a much more grassroots level, backyarding aficionados will be familiar with the output of AngaarTV and its offshoots: a collective of youngsters going by names like Sagar Mysterio and Rakesh Kumar Orton who spend their free time staging delightfully ramshackle and highly committed WWE tributes for people in their local area (check out their incredible take on the Punjabi Prison match, featuring an unexpected run-in which left me and my friends breathless with laughter when we watched it).

Despite all this, where pro wrestling in India is concerned, one name stands above the rest. That name belongs to Dara Singh.

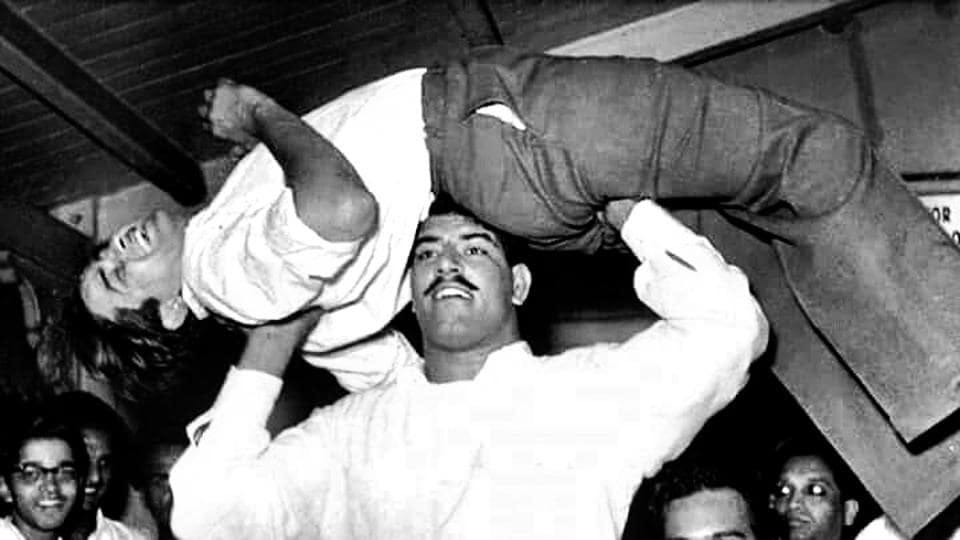

Dara Singh was crowned champion of India in 1954 and defeated the Canadian George Gordienko to become champion of the British Commonwealth in 1959. The peak of his pro wrestling career in his home nation came in 1968, when he fought and defeated the legendary former world champion Lou Thesz not once but twice, drawing 60,000 fans in Bombay and 50,000 in New Delhi. Thesz, not a man given to doling out praise willy-nilly, described Singh in his autobiography as “an authentic wrestler” who was “superbly conditioned” and someone for whom he had no issue doing the job. The series proved a huge critical and commercial success. In Thesz’s words: “The publicity was incredible – newspaper photos and stories every day, movie newsreel crews following me around, huge 10-foot-by-10-foot posters of Dara and me plastered all over the city.”

Singh also excelled abroad. He took Rikidozan to a draw in Singapore in 1955, went Broadway with Thesz a couple of years later for the NWA International Heavyweight Championship at London’s iconic Royal Albert Hall, and in 1975 competed in NJPW’s World League, the forerunner to today’s G1 Climax tournament. He also made an acting career for himself, usually appearing post-retirement as, in the words of a friend of mine from Delhi, “a saucy Punjabi grandpa”. (Amusingly, when I first mentioned to her I’d been reading about Dara Singh, she revealed she wasn’t aware of his wrestling career, which is the Indian equivalent of only knowing Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson from Baywatch.) In 2003 Singh became the first sportsman to be nominated to the Rajya Sabha, the upper house of the Indian parliament, and in 2018 was inducted posthumously into the Legacy Class of the WWE Hall of Fame. It’s fair to say he was a big deal.

A big enough deal to make it into literature. Dara Singh’s name appears in both Salman Rushdie’s 1981’s Booker Prize-winning Midnight’s Children and his 1999 novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet. The references are only brief, but Rushdie uses Singh very effectively as a symbol of Indian nationhood, the attenuated promise of postcoloniality and the effects of globalisation upon former colonies and their people.

We first glimpse the world of Indian wrestling early on in Midnight’s Children, an incidental background detail (“Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium is in sight, with its giant cardboard cut-outs of wrestlers, Bano Devi the Invincible Woman and Dara Singh, mightiest of all...”) as the protagonist Saleem Sinai’s father Ahmed and his shady entrepreneur friend Dr Narlikar race through Bombay to view Narlikar’s get-rich-quick land reclamation scheme. Later, Saleem’s down-on-his-luck movie director uncle Hanif takes him to the stadium to see Singh wrestle:

we're sitting in excellent seats as floodlights dance on the backs of the interlocked wrestlers and I am caught in the unbreakable grip of my uncle's grief, the grief of his failing film career, flop after flop, he'll probably never get a film again But I mustn't let the sadness leak out of my eyes He's butting into my thoughts, hey phaelwan, hey little wrestler, what's dragging your face down, it looks longer than a bad movie, you want channa? pakoras? what? And me shaking my head, No, nothing, Hanif mamu, so that he relaxes, turns away, starts yelling Ohe come on Dara, that's the ticket, give him hell, Dara yara!

Here Rushdie uses the live wrestling experience to prefigure his story’s later chapters. As Midnight’s Children unfolds, Saleem, born “at the precise instant of India’s arrival at independence”, becomes symbolic of the nation not only metaphorically but literally. At the end of the novel Saleem, who has lived through, been impacted upon by and altered the course of so much post-independence history – Bombay’s political and economic evolution, various wars with Pakistan, Indira Gandhi’s state of emergency and its associated human rights abuses – dissolves into fragments, unable to bear the weight of “too much history”:

Yes, they will trample me underfoot, the numbers marching one two three, four hundred million five hundred six, reducing me to specks of voiceless dust, just as, all in good time, they will trample my son who is not my son, and his son who will not be his, and his who will not be his, until the thousand and first generation, until a thousand and one midnights have bestowed their terrible gifts and a thousand and one children have died, because it is the privilege and the curse of midnight's children to be both masters and victims of their times, to forsake privacy and be sucked into the annihilating whirlpool of the multitudes, and to be unable to live or die in peace.

By having the child Saleem put on a brave face so that his uncle can enjoy the catharsis of cheering on Dara Singh, Rushdie provides an early moment in which his protagonist is forced to bear the weight of the adult world’s sorrows and stresses long before his magical realist conclusion (and, we might say, unintentionally lays bare the emotional repression which partially underpins kayfabe).

Rushdie references the “cardboard effigies of wrestlers still tower[ing] above the entrance to Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium” once more in Midnight’s Children, in the final chapter, just before Saleem’s disintegration.[1] The protagonist’s final return to the city of his birth, initially joyful, turns sour as while the wrestling stadium remains intact, much else does not:

the names had changed: where was Reader's Paradise with its stacks of Superman comics? Where, the Band Box Laundry and Bombelli's, with their One Yard Of Chocolates? And, my God, look, atop a two-storey hillock where once the palaces of William Methwold stood wreathed in bougainvillaea and stared proudly out to sea…look at it, a great pink monster of a building, the roseate skyscraper obelisk of the Narlikar women, standing over and obliterating the circus-ring of childhood…yes, it was my Bombay, but also not-mine.

Ultimately, in Saleem’s words, “the past fail[s] to reappear”. The final tragedy of Midnight’s Children is that the India that crushes Saleem under the symbolic weight of its contradictions is also itself dissolving. The juxtaposition of the Vallabhbhai Patel Stadium with these altered not-quite-echoes of the past suggests that while it remains intact for the moment it, too, may follow. Even Dara Singh must retire at some point.

This elegiac mode is also evident in The Ground Beneath Her Feet, which features another narrator who becomes disillusioned with post-independence India and its discontents and ultimately takes his leave of the country (though in this case through emigration, not dissolution). Once again, Rushdie uses Dara Singh to make a point regarding Indian national identity. In the words of the narrator, campaigning photojournalist Rai Merchant:

A kind of India happens everywhere, that’s the truth too; everywhere is terrible and wonder-filled and overwhelming if you open your senses to the actual’s pulsating beat. There are beggars now on London streets. If Bombay is full of amputees, then what, here in New York, of the many mutilations of the soul to be seen on every street corner, in the subway, in City Hall? There are war-wounded here too, but I speak now of the losers in the war of the city itself, the metropolis’s casualties, with bomb craters in their eyes. So lead us not into exotica and deliver us from nostalgia. For Dara Singh read Hulk Hogan, say Tony Bennett instead of Tony Brent, and The Wizard of Oz makes a more powerful transition into colour than anything in the Bollywood canon. Goodbye to India’s hoofers, Vijayantimala, Madhuri Dickshit, so long. I’ll take Kelly. I’ll take Michael Jackson and Paula Abdul and Rogers and Astaire.

Wrestling fans among you will be sceptical of the idea that Dara Singh had anything in common with Hulk Hogan beyond the fact they were both their country’s foremost grappling megastars, and you’d be right. Watch this footage of Singh tying it up with King Kong Czaya – a wrestler about whom, unlike Singh, Lou Thesz did not have good things to say – and you’ll be hard pushed to find anything of the Hulkster’s hot-dogging. But this imperfect mapping of Indian onto American is, I’d argue, deliberate on Rushdie’s part. Inherent within the above passage is an implicit criticism of Rai’s decision to turn his back on the country of his birth and to quit fighting to change it for the better, particularly within the context of the next paragraph:

But if I’m honest I still smell, each night, the sweet jasmine-scented ozone of the Arabian Sea, I still recall my parents’ love of their art dekho city and of each other. They held hands when they thought I wasn’t looking. But of course I was always looking. I still am.

As in Midnight’s Children, Rushdie emphasises the intertwining of one’s personal fate and that of the nation, and suggests that seeking to sever this thread is futile. But The Ground Beneath Her Feet, set in an era in which India and the world in general had become more globalised than in 1981, not only critiques colonialism but globalisation’s flattening affect. Rai is trying to convince himself more than anyone that “a kind of India happens everywhere”. We as readers can see through him, possessed with the knowledge that Michael Jackson and Paula Abdul are hardly like-for-like replacements for Vijayantimala and Madhuri Dickshit, that Tony Bennett isn’t Tony Brent, and – if we know our wrestling – that Dara Singh isn’t simply the Indian Hulk Hogan. Thesz would never have put Hogan over for a start.

Not all of Rushdie’s wrestling references are deep. In the scene in The Satanic Verses where Mahound (his fictional analogue for the prophet Muhammad and one of the things that got him fatwaed) grapples with the angel Gibreel in the desert, the narrative states: “Two falls, two submissions or a knockout will decide.” Seasoned World of Sport watchers will recognise this as an allusion to the Mountevans Rules that formed the basis of British wrestling for decades. It’s a good bit, but overall pretty throwaway. By contrast, the wrestling allusions in Midnight’s Children and The Ground Beneath Her Feet demonstrate that Rushdie’s fiction is at its best when using cultural references to interrogate the fault lines of nationhood, identity, politics, economics, religion and more besides.

Furthermore, in these two novels he uses the same pop cultural figure to critique the trajectory of post-independence India and its people in two different ways. Something unspoken across Midnight’s Children and The Ground Beneath Her Feet – and only readily apparent if you consider both novels in conjunction through a metatextual lens – is that the fact Rushdie is able to do this suggests that Dara Singh, just like Saleem Sinai, was a person who found himself imbued with a nation’s hopes, dreams, histories and agonies. Yet, unlike Saleem, Singh found himself able to bear the burden, to become a fine prism through which these energies could become refracted for writers and fans alike to bathe in, not a pane of shattered glass crunched underfoot by hundreds of millions. This is, perhaps, the shield afforded by celebrity, physical strength and being able to, in a literal and metaphorical sense, “book one’s own stories”.

But the elegiac tone of the way in which Rushdie, albeit briefly, depicts Singh and Indian wrestling also indicates that he considers the sport’s status within the national imaginary to be part and parcel of the country’s deliquescence. It is as a means of exploring these dynamics in the country of his birth that wrestling has value for him as a cultural product. Moreover, the recent history of Indian wrestling suggests that The Ground Beneath Her Feet’s critique of globalisation carries some justification. Rushdie’s fiction is carnivalesque, entertaining, sometimes aggravating and, in this case and many others, prescient. After all, Dara Singh was ultimately replaced by Hulk Hogan, or the WWE at least, and as charming as Ring Ka King and AngaarTV are, they too owe a great debt to Western pro wrestling. The idea of an Indian wrestling company focused on Indian talent drawing 60,000 fans to a stadium show seems as fantastical as Rushdie’s magical realism, and to younger Indians, their country’s greatest ever wrestling star is merely a saucy Punjabi grandpa.

[1] Significantly, the stadium is named after one of the primary architects of Indian independence.