Watching Deathmatches with Astrophysicists: What I Learned at Korakuen Hall

Or, Why You Should Show Your Friends Gabaiji-chan If You Want to Get Them Into Japanese Pro Wrestling

Front Matter

The ringside images used here are linked to the Twitter accounts responsible for them: simply click through to bring up the original post. If you are a photographer whose image I have used here, and you do not grant me permission to reproduce your work, please let me know (Twitter: @FlupkeDiFlupke) and I will remove it. Thanks!

写真家さん、ここにイメージが写すことが許可しなければ聞いて下さって私は大至急除きます (ツイターの @FlupkeDiFlupke です)。ありがとうございます!

Subscribe now!

Subscribe to Marshmallow Bomb for free to receive all our posts direct to your inbox, or donate $5 a month to access the full archive. A portion of every subscription supports Amazon Frontlines, an organisation dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to defend their way of life, the Amazon rainforest, and our climate future.

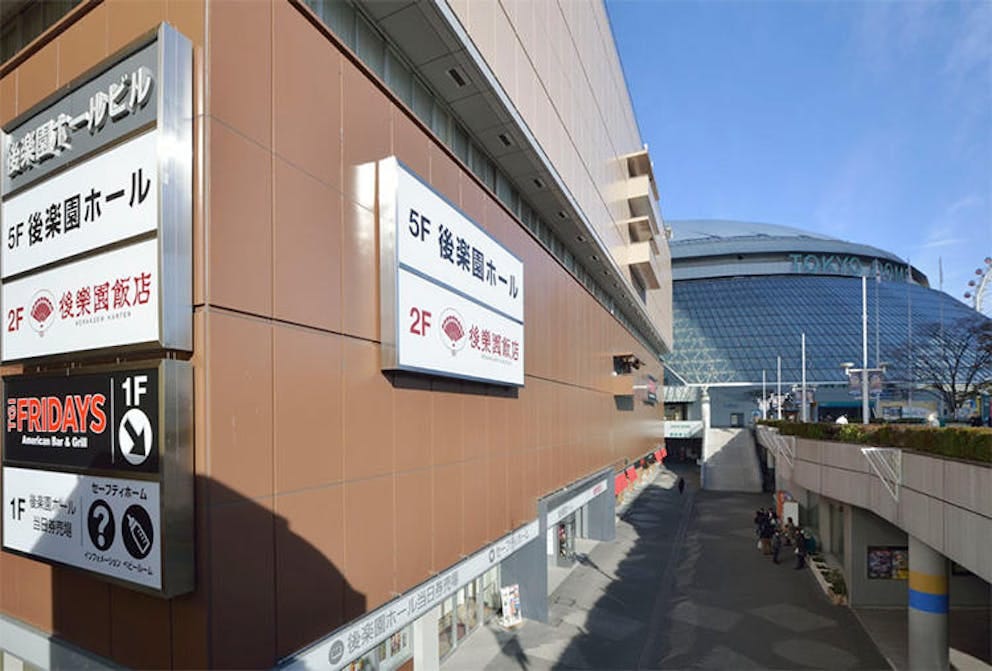

If you take the subway to Iidabashi Station in Tokyo and walk for around five minutes in a north-easterly direction, you’ll come across the Tokyo Dome. This baseball stadium and occasional wrestling venue is a colossal white edifice whose appearance earns it the nickname “Big Egg”, a tourist attraction significant enough to appear in my Lonely Planet guide to the city. It’s an awe-inspiring sight, especially when lit up at night, limned with neon green.

But just over the road, there’s an unremarkable brown building. You could easily not notice it was there, your eyes entranced by the illuminated ballpark like a fly about to do the job to a bug zapper. Take the lift or stairs up to its fifth floor and you will find the most famous wrestling arena in all of Japan.

As you can imagine, what with me being the host of a Japanese wrestling podcast and everything, going to a show at Korakuen Hall was very high up my bucket list for some time. I say was, because it’s not anymore. I finally got to live my dream – not once but three times! – during my recent trip to Japan with my Puro Pourri Podcast comrade and life partner Sarah, and we took in a ChocoPro at the colosseum that is Ichigaya Chocolate Square for good measure. (We also found the time to do a bit of sightseeing.) I enjoyed myself a lot at these shows, but I also learned a lot, primarily because at the first of these events we were joined by a couple of interlopers who made me appreciate the intoxicating spectacle of Japanese pro wrestling anew and reminded me that newcomers to the sport have just as much insight to offer as us old stagers.

The Newbies

I used to play in my university jazz orchestra, for my sins. I’m not in touch with most of the old gang now, but I’ve always made a point of staying in touch with my fellow trumpeter Abi, who is always great company and with whom I share a deeply held yen for Pokémon. I’d last met up with her in October 2022, just before she moved to Chile to work at a very prestigious observatory (she’s an astrophysicist, which is scientifically proven to be one of the most badass jobs it’s possible to have). I thought it’d be years before we got to hang out again. But a couple of weeks before Sarah and I were due to fly to Tokyo I was delighted to receive a message from Abi telling me that her and her partner James (also an astrophysicist) were going to be in Tokyo at the same time as us. The next message read: “I want to see some wrestling and I don’t know where to start”. This was, needless to say, as a sweetly played clarinet to my ears.

I looked at the indispensable Puwota calendar to see what would be on during the few days our paths were due to cross, and by far the most appetising option was Prominence’s first anniversary show, which was also their first Korakuen date. The only snag was that it was taking place in the evening of the day we landed, so there was a risk that Sarah and I would be too jetlagged to enjoy ourselves properly, but I would run through a wall for my friends, so sitting through what would probably be at the very least a good show while suffering from moderate-to-severe sleep deprivation was the least I could do.

The announced card looked good on paper, especially an extremely appetising Suzu Suzuki-Jun Kasai bout, but what excited me most about the prospect of Prominence was how Abi and James would react to it. Neither of them had seen puro before, their experience of wrestling limited to childhood viewing of WWE (in James’ case) and the odd PPV watch party at my place (in Abi’s). The fascination when introducing newcomers to an unfamiliar wrestling product always lies in what they’ll latch onto. Sometimes it’s completely out of whack with what you and the live audience are into; I remember watching Elimination Chamber 2014 with the jazz orchestra lot, who completely failed to engage with the Daniel Bryan underdog story that had become the hottest thing in the company for smarks and casuals alike but howled with delight at every single word that came out of Bad News Barrett’s mouth. And sometimes their reactions align completely with yours, as when I took my mum to an EVE show and discovered during the train ride home that our rankings of the night’s matches were identical.

Those of us who obsess over wrestling to a sometimes unhealthy degree can’t imagine ourselves into the head of a novice, just as you can’t be shocked that Bruce Willis is a ghost on a second viewing of The Sixth Sense. Having Abi and James in tow allowed me the chance to appreciate the sport I love through new eyes. What’s more, Prominence was to be their first live puro show but their first live wrestling full stop. All told, I was probably more excited for them to experience the event than they were.

I imparted two pieces of sage advice unto Abi and James before we went through those hallowed doors: 1) under no circumstances should you order the famously crap Korakuen Hall chicken nuggets; and 2) Prominence is a deathmatch promotion, and if some of the matches seem visceral to you, it’s important to remember that nobody is forcing these people to cut each other up with skewers and broken glass, they are just sickos and they love it. (Case in point, the photos of Hikari Noa taken after her light tube match with Sawyer Wreck a week later, her back shredded to ribbons and a proud, joyous smile on her face.) With that done, we took our seats and awaited the opening contest.

The Old Man

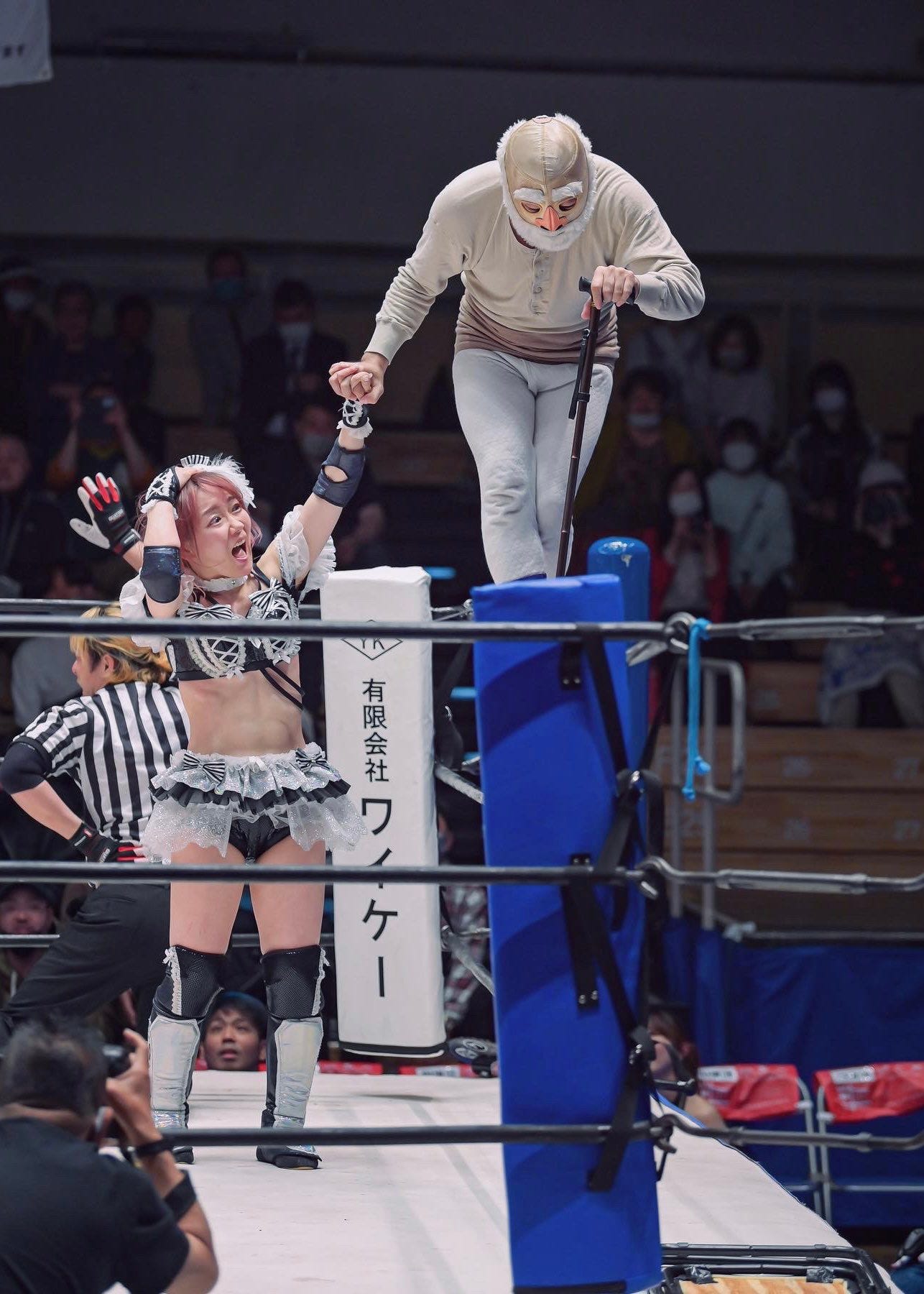

I couldn’t have wished for my friends to taste a more perfect introduction to puro. The show began with a ten-person battle royal with a lineup comprised of indie freelancers and FREEDOMS guys. Miyako Matsumoto, Cherry, Itsuki Aoki, Sakura Hirota, Miyuki Takase, Orca Uto, Choun Shiryu, Super Hardcore Machine and Toshiyuki Sakuda all had chances to impress, but by far and away the most popular competitor amongst our group was Gabaiji-chan, a masked wrestler whose gimmick is that he’s a doddery old man who is extremely slow and rather feeble. Abi and James loved Gabaiji-chan. They were still talking about him when we said our goodbyes at the end of the night. Gabaiji-chan’s silly pratfalls and bumbling brought a greater amount of joy and laughter into their lives than I ever thought possible.

That’s the first lesson I drew from Prominence: that contrary to what Jim Cornette and his legion of drooling morons would have you believe, dumb comedy absolutely can attract people to wrestling. In fact, I’ll go a step further. I think it’s the best type of wrestling to show a newbie.

The issue of what match you should show a newcomer to wrestling, or to a particular wrestling scene, is a hoary old debate within the fandom. I’ve heard people argue that one of the Katsuyori Shibata/Tomohiro Ishii murderfests is an ideal first puro match, others that the Young Bucks are best placed to entice the AEW-curious. Dave Meltzer once posited that Villano III and Atlantis’ famous mask vs. mask match from 2000 was the one, which is very Dave.

All of these approaches are fraught with danger, in my view. I can imagine someone watching Shibata and Ishii clatter the shit out of each other and wonder why they’re not just watching UFC, and I can imagine someone watching the Brothers Jackson’s flip-de-doos and wonder why they’re not just watching gymnastics. Someone unfamiliar with lucha might not grasp the significance of the apuestas stipulation. You get the picture.

Conversely, I don’t often hear people suggest comedy matches as a gateway drug to the mat business. Much of the resistance arises from two main objections. The first is that comedy wrestling functions as a deconstruction of quote-unquote “normal” wrestling, therefore you should expose people to the latter first, so that they appreciate what the former is parodying. A respectable take, but one I feel is misguided, because it presupposes that viewers will necessarily see comedy wrestling as a subgenre of wrestling rather than a subgenre of comedy. But what the antics of a Gabaiji-chan or a Kuishinbo Kamen or a Sakura Hirota are, at their core, is slapstick, and slapstick is instantly comprehensible to the newbie. Its appeal travels across time, which is why Buster Keaton movies are still hilarious a century after they were made, and it travels across distance, which is why Mr. Bean is famously over like rover in Afghanistan. Make people piss themselves laughing at the outset of your wrestling show, as Gabaiji-chan did Abi and James, and you’ve got them in the palm of your hand for the rest of the night. It’s the entertainment business, after all.

The second objection seems to originate from the worry that people won’t take wrestling seriously. I do have a certain amount of sympathy with the impetus behind this; it’s always worth taking your hobbies seriously, even the daft or outré ones. But just because your friends aren’t familiar with your cherished wrestling scene doesn’t mean they won’t come into it with a set of preconceptions. Believe me, showing them some silly bollocks like a Gabaiji-chan match isn’t going to upend their expectations, because they most likely already think that wrestling is silly bollocks. And they’re right. It is silly bollocks (and I mean this as a compliment). So roll with it. Get over this insecurity that your friends laughing at wrestling means they’re laughing at you. Because they’re not laughing at wrestling, they’re laughing with wrestling. I’m not saying you should introduce people to NJPW by showing them Toru Yano over Kazuchika Okada or that you should introduce people to AEW by showing them Orange Cassidy over Kenny Omega, but also, I very much am saying it.

After the battle royal, we got a hardcore tag match featuring ladders, chairs, and a finish which saw the unlucky Cohaku take a Death Valley Bomb onto a wooden stool. Afterwards I leaned over to Abi, who I’d seen wincing at a fair few points while this was unfolding, and said, “this isn’t even the stuff I warned you about”.

The Violence

A few years ago Suzu Suzuki gave an interview to an English language podcast during which, when she brought up the subject of deathmatches, the host (who I’m not going to dignify by naming him or his show) told her she shouldn’t do deathmatches so she could keep her face looking nice; both creepy and patronising, an impressive economy of ick. It still makes me mad to think about how someone could get access to such a special performer and then do that with it. But such attitudes are all too common. In 2021, in the face of online criticism after an especially violent bout against Masashi Takeda – who also featured on Prominence’s Korakuen card – both he and Suzuki were forced to issue statements defending her right to work this type of match.

By asserting that Suzuki was worthy of being treated like any other deathmatch wrestler regardless of her gender and young age, Takeda – the man who had just spent an evening carving her open with broken glass and barbed wire and other instruments of mayhem – showed her far more respect than the man who didn’t want her to shed her own blood and permanently scar her back. Perhaps that seems perverse, but a) that’s wrestling for you, and b) you cannot call yourself a supporter of women’s wrestling – or indeed a supporter of women in general – if you circumscribe what type of wrestling you are happy to see them do, even in the face of female performers’ own wishes to do it.

Abi and James, not being dickheads, grasped all this perfectly well. They recognised what they were seeing not as a form of torture but as a form of art which needed to be treated on its own merits, the same as any other match on the card. My friends’ anxiety on Suzuki’s behalf was not for her real-life wellbeing, which they correctly understood to be her business and hers alone, but whether she could win. Not “get her out of the ring” but, as Abi yelled at one point, “get his ass!”

Two things helped enhance the spectacle. Firstly, the card’s layout. The show built beautifully from the light-hearted battle royal, through a pair of contests which added more intense action while maintaining a comedic vibe, to a hard-hitting and deadly serious big lass fight between Yuu and Hiragi Kurumi, to the deathmatches. The gradual escalation really heightened the effect of the ultraviolence when it arrived (I will add light tube matches to the list of things that would be a worse introduction to puro than Gabaiji-chan).

Additionally, the match absolutely ruled. Over fifteen minutes, Suzu Suzuki and Jun Kasai expertly told a classic underdog vs. wily veteran story that, like the slapstick in the opener, was immediately comprehensible even without knowledge of the combatants, tropes or wider industry context; it was just that the wrestlers’ way of telling it was to fuck each other up with glass. Kasai is getting on in years, but he knows what he’s about and what he’s still capable of, and remains a master storyteller. Suzuki, meanwhile, is a marvel. There is nothing more to say on the subject. And I know she’s a marvel because Abi and James, who had never heard of her a few hours prior, lived and died by her every move, and audibly groaned in disappointment when Kasai finally put her down for the three-count.

The show ended up being a turning point in Prominence’s fledgling history, though I didn’t know it at the time. After the bout, Kasai presented Suzuki with a bouquet of flowers and the pair shared a tender moment of mutual respect and admiration whose beauty was by no means diminished by the fact they were both covered in cuts and blood. Then Suzuki cut a promo, whose words I didn’t manage to make out, my comprehension of spoken Japanese not being great. It turned out that she’d announced she was leaving the promotion.

Suzuki joined Stardom’s national tour soon after, and I expect that to become her home for the foreseeable future. It didn’t come as a shock; she’s an undeniable star and that company’s management team, whatever their faults, know someone they can make money with when they see it. It’s a blow to Prominence, and an especially bitter pill to swallow after their biggest show of all time was so well-received, but going by the crowd’s reaction as Risa Sera and Akane Fujita brutalised each other in the main event, I reckon they’ll be fine. I sure hope so. There has to be a place within joshi for this kind of thing, however unpalatable it might be to some.

Suzuki made clear that quitting Prominence doesn’t mean she’s going to stop doing deathmatches. Clearly she considers a Stardom contract that doesn’t allow her to bleed to be a Faustian bargain. And quite right. Her performance against Kasai at Korakuen that night demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt that the truly great deathmatch workers are truly great workers, period. They use weapons not as a crutch but as a way of telling stories that are vivid, timeless and honest. They can draw in people who have never seen a light tube deathmatch in their lives and, rather than repel them, can have them shouting their lungs out, willing them to push through the gore and emerge victorious. As my friends’ reactions to Prominence proved, if you’re a world class wrestler you can make believers out of anyone, whether you want people to believe in your skill, heart and determination in the face of adversity, or whether you simply want them to believe you’re a feeble old man.