My Hero Mahiro, or How TJPW (Somehow) Rekindled My Love for Mahjong

Godalming, Ariake, and the bittersweet feeling of losing at something you love

Front Matter

The photographs used in this article are linked to the Twitter accounts responsible for them: simply click through to bring up the original post. If you are a photographer whose image I have used here, and you do not grant me permission to reproduce your work, please let me know (Twitter: @FlupkeDiFlupke) and I will remove it. Thanks!

写真家さん、ここにイメージが写すことが許可しなければ聞いて下さって私は大至急除きます (ツイターの @FlupkeDiFlupke です)。ありがとうございます!

Grand Princess week concludes! Before digging into this piece, why not check out Stuart’s comprehensive review of the show, Flupke’s longer-form thoughts, WB’s vital interpretation of the main event as queer love story, and John’s ode to Suzume and Arisa Endo’s opener?

Subscribe now!

Subscribe to Marshmallow Bomb for free to receive all our posts direct to your inbox, or donate $5 a month to access the full archive. A portion of every subscription supports Amazon Frontlines, an organisation dedicated to working with Indigenous peoples to defend their way of life, the Amazon rainforest, and our climate future.

北

2020 was the worst year of my life, and I’m guessing it may well have been the worst year of your life too. I know a lot of people claim to have enjoyed lockdown because “it gave me a chance to focus on the small, important things and find true happiness”, but these people all have big comfortable houses, read the Guardian and describe themselves as “a bit of a lefty” but voted Lib Dem in 2019, so they can be safely ignored. It’s fairer to say that most of us survived rather than thrived, and the things we found to do with our days functioned primarily as coping mechanisms. Some folks took up crochet, others bought a Switch and spent months slowly destroying their relationship with their partner over the course of an Overcooked! playthrough. My lockdown hobby, however, was mahjong.

In a weird way, I got into mahjong because of wrestling. I bought Yakuza 6 on the grounds that it featured guest appearances by NJPW main event superstars including Hiroshi Tanahashi, Kazuchika Okada and Toru Yano. I’m the sort of person who likes to get my money’s worth, so I decided I would try and complete all the side quests and minigames as well as the main story. One of those minigames was riichi mahjong.[1] After having got all the achievements for it, I realised that a) I finally understood the rules, and b) I wanted to continue with the game. I searched out a place to play online, and now here I am three years later, a two-time member of the UK squad at the International Online Riichi Mahjong Competition, a former team captain in the Australian Riichi Mahjong Association League, and I don’t get the kanji for the numbers six and eight mixed up anymore. It’s fair to say things have gotten out of hand.

As for what any of this has to do with wrestling, that’s a question I should probably answer. It’s become a running joke on the Puro Pourri Podcast that “everything is pro wrestling”, and to this end we have released episodes teasing out the ways in which other sporting interests of ours (football, robot combat) dovetail with our favourite faux sport. I always considered #MahjongIsProWrestling to be a bit of a stretch, and yet my recent reflections on the game, my own participation in it, and TJPW’s recent Grand Princess show have made me think twice; both in terms of how mahjong and wrestling mirror each other as entertainment products and as disciplines.

西

The basic rules of mahjong are not as complicated as you might suppose. There are three suits (characters, dots, bamboos) of tiles numbered one to nine, then you have tiles representing the four winds, and finally tiles representing red, green and white dragons. There are four copies of each of these in a set, making 136 tiles in total. A hand consists of fourteen tiles, and on each turn the four players will draw one from the pool and then discard one, with the aim of assembling a hand that consists of four sets of three (either three identical tiles or three consecutive numbers in the same suit), and a pair. There are exceptions to the rule; you can win if you have seven different pairs of tiles, and there’s an especially rare hand called Thirteen Orphans whose mechanics I won’t get into, but that’s the long and short of it. After you win a hand, you’ll be given a score based on what tiles you have, gaining points for things like a triplet of the same dragon, or having three triplets of the same number in each suit, and then you’ll play until everyone has had two goes at being the dealer, at which point the players are ranked from first to fourth based on how many points they have overall.

This might not seem like a natural spectator sport, but the professional mahjong scene in Japan has a strong following. Mahjong isn’t a work – although it’s possible to cheat, and the many etiquette rules, such as those governing how you shuffle and handle the tiles, are designed to prevent any sleight-of-hand tricks, though these are unheard of in today’s pro games – but in other respects the ways in which it is presented as an entertainment product will be very familiar to those of us who know the puro industry.

The calendar, which consists of a number of round-robin leagues and shorter-duration tournaments, was shaken up in 2018 by the M.League, a new annual tournament broadcast on ABEMA TV (which also sponsors DDT/TJPW and hosts their variety content). Rather than formal suits and dresses, the players – who are sorted into eight teams of four, all with corporate sponsors – wear colourful shirts that bring to mind one-day cricket kits, and the presentation is all bright lights and dramatic music. Some fans love it for its production values and accessibility, while others are turned off by the gimmickry and have criticised the commentary for lack of insight. Now which company does that sound like?

Away from the game itself, players hustle and grind, just as wrestlers do. Some will supplement their fees from competitive play by working as guest pros at mahjong parlours, which will do good business from punters hoping to play a game against their favourites, and the most well-known can derive further income from such avenues as variety show appearances or photobooks. Furthermore, while some can use mahjong to gain a foothold in the entertainment industry, others have come to the game from the world of showbusiness. Sayaka Okada worked as a model and didn’t take up the game in earnest until the age of 21, while Masato Hagiwara, the voice of the title character in the mahjong anime Akagi, became so notorious as the strongest player amongst those involved in that particular subgenre that he eventually turned pro. (Hagiwara also played Rikidozan’s secretary in the 2004 film Rikidozan: A Hero Extraordinaire, so there’s another wrestling connection for you.)

Professional wrestlers do seem to enjoy confounding the stereotypical view that they’re stegosaurus-brained meatheads, and there are several confirmed mahjong fans in the Japanese wrestling business. For example, STARDOM’s Unagi Sayaka uploaded an image last year of herself playing at a parlour, in what we can only hope was her full ring outfit. However, TJPW appears to be the real hotbed. Haruna Neko has on more than one occasion posted screenshots of her online games to Twitter, while Suzume’s Instagram page carried a photo of her settling down for a game with the wee cat (copyright: Stuart Iversen) and Mahiro Kiryu. Kiryu is without a doubt the biggest mahjong otaku on the scene. Her 8x10s have frequently featured her posing with mahjong tiles, she posts videos of her coolest hands to her socials, she is an avid M.League fan who is always tweeting about her favourite players, and in 2022 she partnered professional Taro Suzuki at a pro-am event. I like to imagine these four women whiling away the hours at the dojo drawing and discarding tiles, back when Unagi was with the Teej. I hope they’ve managed to replace her. Three-player mahjong just isn’t the same.

But while we may highlight the connections between Japan’s mahjong and wrestling industries all we want, the main way in which I relate to wrestling as an amateur mahjong player comes from how the game has made me appreciate the journey of becoming a wrestler. I’ll never take a back bump in my life – at least not intentionally – but the grind, the mental torture, the feeling that not only will you never reach the top but you’re barely worthy of the midcard? Oh baby, I’ve experienced that in spades. And to that end, let me take you back to last weekend.

南

Because I started playing mahjong during lockdown, I had to wait a while for my first in-person tournament, though I scratched the itch by playing in online ones. In the summer of 2022, I finally got my chance, travelling to the small town of Godalming, the headquarters of the UK Mahjong Association, for the UK Open. I made several new friends, put some names to faces I had previous only seen in the form of Discord avatars, and placed a very respectable 17th out of 48. Having had this taste, I decided I wanted more, so jumped at the chance to enter last weekend’s spring tournament in Twickenham.

Day one didn’t go badly. I placed second in the first game and was one tile away from winning, then I got a last place in Game 2, which I wrote off as my one designated shit result for the weekend (lol, lmao). A narrow first place followed, and I ended the day with a third, which put me in the middle of the pack in the tournament standings. I was ready to chill with my friends at night and kick on towards the top of the table in the morning. As for how that went, I will refer you to my previous “lol, lmao” comment.

As might be inferred from my earlier description, luck is a big factor in mahjong. Sometimes an incredible hand will fall into your lap more or less fully formed, but on other occasions you will literally not be able to win because your draws are so bad. A team of academics once worked out how many hands a group of mahjong players would need to play in order for the luck to even itself out, and they concluded it was about a hundred. At least on the European scene, almost all tournaments give you eight games at most. From one viewpoint this adds to the fun; I could beat a table of three top professionals with fortune on my side, whereas I would never be able to beat a chess grandmaster, for example (and I have tried!). However, losing a game feels doubly bad because you are liable to get screwed over not only by your own errors and inaccuracies but by the whims of fate that can leave you feeling utterly helpless. And when you go on a winning streak, even when you qualify to represent your country, the risk of impostor syndrome is never far away. Did you play well or just get lucky? Fun!

But what’s even worse than losing through misfortune or a slightly suboptimal move, or a combination thereof, is when you just. Simply. Fuck it.

In Game 5, running in last place but with one tile left to complete a haneman (this is Japanese for “shitloads of points”), I got overexcited and erroneously called a win when an opponent discarded a nine of dots, whereas actually what I needed was a three or a six. On the very next hand, head utterly gone, I declared riichi (i.e. that I was a tile away from victory) when I wasn’t, which led to 20,000 points being docked from my score for the tournament. You might think that sounds like a lot, and you’d be right. I somehow managed not to come last in this game, but it didn’t raise my mood one iota, nor did it help when I overcame a large deficit on the final hand to lift myself from fourth to third in Game 6. Another third place – my fourth on the bounce – followed in an albeit entertaining final game, and I ended the weekend ranked a lowly 51st out of 64 players.

To reiterate once again: mahjong is in large part a game of luck. I know better than to read too much into one bad tournament result. But while it would have been one thing if I’d had a low finish because I didn’t get good draws, or because my opponents played well (and both of those things were certainly the case), the fact that such an elementary error – which I had never made before in any in-person game I’d played! – had cost me so dearly sickened me to my very core. I spent much of the day with my head lost in a black fog congealed from self-loathing, and almost shed tears at one point. I was barely able to enjoy my friends’ company between games and after the prize-giving. The four-hour journey back up north didn’t help matters. It’s a long time to spend kicking yourself and wondering why the hell you even bother with this stupid pastime.

In an effort to cheer myself up, I stuck TJPW Grand Princess on the TV when I got home. The opener of Arisu Endo vs. Suzume was excellent, but I remained distracted while watching it. It wasn’t until the second match, the one with all the rookies, that a shaft of light poked through the gloom.

東

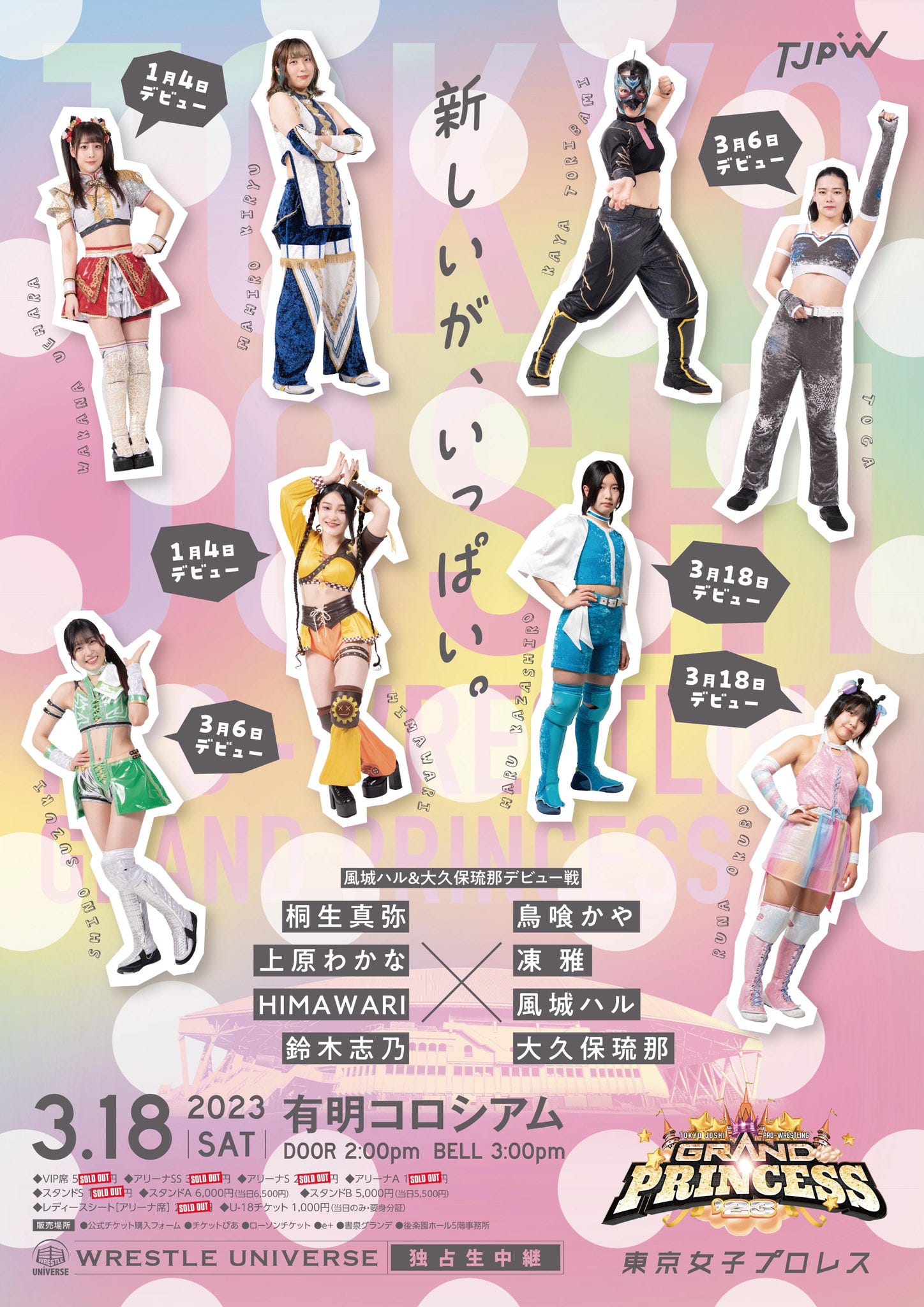

I wrote in my preview of the show that Mahiro Kiryu, HIMAWARI, Shino Suzuki and Wakana Uehara vs. Kaya Toribami, Toga, Runa Okubo and Hazu Kazeshiro would probably be a rough watch, and I was right. This isn’t a slight on the performers at all; all but two of them are a few months into their careers, and two were making their debuts. It was never going to be 6/3/94. But it’s probably the most I’ve been spiritually nourished by a not very good wrestling match.

As I watched these young tyros move at half speed, run the ropes awkwardly and throw strikes that barely connected, I felt deeply and profoundly inspired by their efforts, clumsy though they were. It was a welcome reminder that nothing worth doing comes easily, and that everyone has to begin at the foot of the mountain. My early successes in mahjong had blinded me to the fact that I still have so much to learn, as these wrestlers do. More than anything, I drew great comfort and resolve from Kiryu. She started out at the HIMAWARI / Shino / Uehara / Toga / Okubo / Kazeshiro level, and now here she is, hardly a main event player or a Best Technical Wrestler candidate, but a solid hand the company trusts to guide half a dozen newbies through a complex match format in front of the biggest crowd of the year. When you watch her, you can see the progress it’s possible to make if you just try hard. That my feelings about mahjong should be soothed by a match involving the biggest mahjong nerd in the Japanese wrestling scene seemed apt somehow. I don’t know Mahiro Kiryu, but I hope she’d approve.

To be honest, I don’t know if I will ever reach the level that I want to in mahjong. My philosophy vis-à-vis my hobbies is that I would rather be quite good at multiple things than incredibly good at one thing, because it takes the same amount of time, and it gives your life more variety. The other hats I wear include novelist, essayist, podcaster, quizzer, linguist and musician, and I wouldn’t want to give any of them up. I probably could become a bona fide mahjong expert if I put in enough hours, learn the theory, internalise the probability tables and master the fine balance of risk and reward, just as I’m sure I have it in me to cultivate a Chaser-level general knowledge brain, or become near-fluent in Japanese, or learn to play the bass guitar like Geddy Lee. But the amount of time and effort needed to do any of these would mean dropping so much stuff that gives me pleasure (including much of my wrestling fandom, which is obviously non-negotiable), and I simply do not want to do that. It means I’ll always be susceptible to the frustration of not being as good as the people who devote themselves to these pursuits entirely, but that’s the choice I’ve made. Knowing I’ll be forever beset by feelings of inadequacy is scary, but the thought of giving myself over to one thing and one thing only scares me more.

And that just makes me appreciate these rookie wrestlers even better. With their full schedule, higher pay and dedicated dojo, they have the potential to reach a level of proficiency that is beyond all but a few of the industry’s part-time weekend warriors. But in return they will have to give professional wrestling their lives. They’ll have to lift weights, take bumps, acquire an arsenal of techniques, develop their cardio, eat right, sign photos, meet fans, travel long distances and do all the menial tasks asked of them by their senpai, fighting through physical pain and mental exhaustion every single day. I can’t begin to imagine doing that. But my mahjong career has made me able to appreciate and admire it more keenly than I ever have before.

I knew TJPW Grand Princess would be a great show, but I didn’t expect to come away from it having learned something about myself and the interests that define me. It impressed upon me that not only are mahjong and wrestling both entertainment products with similarities and connections between them, they both require the same kind of respect and discipline from their practitioners. You have to develop your skills so that you can win and progress, sure, but also so that you can mitigate the risk to you from bad luck - whether it’s a run of unwanted tiles or a blown spot - and know you can bounce back when these things do happen. And watching Mahiro Kiryu marshal her team of rookies made me realise that not only did I need to put in the work if I wanted to reach something approaching my desired level, I wanted to do it. The reason mahjong hurts so much when I fall short is because I love it. When I fail, I feel like I’ve not only let myself down but the game itself. Like wrestling, it’ll break your heart, but you can’t stay away because you know how good it feels when things go as they’re meant to.

That, in the end, is the game.

[1] Riichi mahjong is the name for the specific Japanese ruleset. A riichi is a bet of 1000 points that you can place if you are one tile away from completing your hand, which gives you the potential of a higher score at the cost of “locking in” your hand so that you must discard every tile you draw if it is not one that would net you the win.